Authors: Marisa Vella, Alan Sciberras Narmaniya, Francesca Micallef

Published Online: 01-12-2021 | Sourced From: MCAST Journal of Applied Research & Practice

Volume: 5, No.: 2, 2021

Abstract: Older people may be unable to maintain adequate hydration due to decreased fluid intake and increased fluid loss. Residents in care home settings are particularly vulnerable and at an increased risk of dehydration. This is associated with poor outcomes and can lead to severe consequences. Local data on hydration practices within residential care homes is scarce. We therefore sought out to explore evidence on hydration practices, with a view to inform local practice and identify any gaps for future research. A scoping review was conducted and guided by the methodological framework of Arksey and O’Malley (2005). A search of ten databases: CINAHL, ProQuest: Health Research Premium Collection, SAGE Premier, Cochrane Library, Springer Journals, WILEY Interscience, BioMed Central, Science Direct Freedom Collection, PubMed (Medline), and Northumbria University Library Search, yielded 36,692 citations, of which 11 papers were selected. Articles from 2015, available in full-text and English language, conducted in Europe and published in peer-reviewed journals, were included in the review. The final 11 papers were subjected to data charting, followed by qualitative thematic analysis, and presented as a narrative synthesis. The three main emerging themes include strategies to promote hydration, assessment of hydration status and interventions that promote hydration. Challenges in reducing dehydration, implementing consistent assessment techniques and interventions remain heterogeneous, thus leaving gaps and uncertainty in standards and benchmarks that will support hydration practices in residential care home settings. Future research on addressing individual needs of residents adopting a person-centred approach is highly recommended.

Keywords: Elderly, older adults, hydration care, promoting hydration, dehydration, residential care.

Background

Drinking water and other fluids is essential to health and well-being regardless of the individual or their situation (Godfrey et al. 2012). Water is the major single constituent of the human body, making up more than 50% of total body mass (Masot et al. 2018). Daily adequate water consumption to sustain euhydration is questionably the most essential nutrient prerequisite for human beings. Within a margin of error, the body controls the maintenance of body fluid equilibrium, particularly that of the plasma volume, through mechanisms that stimulate thirst and/or alter the frequency of urine production (Craig 2011). Nevertheless, older adults are particularly at risk of dehydration due to decreased fluid intake and increased fluid loss, thus making older people more vulnerable to water imbalance (Mentes 2013).

The Dehydration Council defined dehydration as “a complex condition resulting in a reduction in total body water. This could be primarily due to water deficit (water loss dehydration or hypernatremia) or to both a salt and water deficit (salt loss dehydrationor hyponatraemia)” (Thomas et al. 2008: p. 293). According to Bourdel-Marchasson et al. (2004), dehydration is a common condition amongst older people with hypernatremia being the most common type (Thomas et al. 2008). Older people have a higher risk of dehydration for a number of clinical and sociodemographic reasons and also due to limitations inflicted by their cognitive and functional state (Schols et al. 2009). These factors are inclined to be further exacerbated by chronic illnesses and the physiological changes triggered by the ageing process (Godfrey et al. 2012). In accordance, the National Institute of Health Care and Excellence (NICE 2013) emphasised that dehydration is connected to increased morbidity and mortality, with an increased risk of falls, exacerbations of chronic conditions and confusion, and poor end of life care. Older adults suffering from dementia are predominantly at high risk of developing dehydration (Paulis et al. 2018) with reduced ability to remember to drink and forgetting to drink when offered with a beverage, being amongst the key problems (Shaw and Cook 2017).

Various studies reported high levels of dehydration in older people who reside in nursing homes. Its prevalence varies from 12% to 50% (Hooper et al. 2016; Wolff et al. 2015; Vandervoort et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2011; Mentes 2006). Specifically, in a study by the Dehydration Recognition in our Elders (DRIE), carried out in the United Kingdom, the prevalence of dehydration was reported to be 20% (DRIE 2016). In addition, the Hydration for Health Initiative (2012) also recommended that between 50%-92% of older adult care home residents have inadequate fluid intake because the residents only drink two to four glasses daily, thus exposing them to suboptimal hydration (Gasper 2011; Woodward 2007). According to Godfrey et al. (2012) drinking is a complex behaviour comprising multiple physical and psychological aspects played out in diverse social environments. Notwithstanding what Godfrey et al. (2012) underlined, Robinson and Rosher (2002) highlighted that an effective intervention to ensure continuously optimum hydration is to increase the amount of fluids being consumed. Indeed, the significance of staff frequently offering beverages and diligently encouraging residents to ingest that drink have been recognised as vital factors in lessening the incidence of dehydration (Robinson and Rosher 2002; Simmons, Alessi and Schnelle 2001).

Cook et al. (2019) looked at hydration practices, as well as practitioner experiences and perspectives within older adult care homes in the UK. Their study showed that care home staff employ various strategies, such as encouraging and prompting residents to drink, social interaction, environmental stimuli, and drink related activities, to stimulate hydration amongst residents. The authors observed that there is a strong social aspect when promoting hydration, as many hydration strategies were linked to social activities and/or gatherings. In fact, other researchers have made similar observations and have highlighted the importance of staff regularly offering beverages and diligently prompting and encouraging residents to consume drinks (Simmons, Alessi and Schelle 2001; Robinson and Rosher 2002). In their systematic review, Bunn et al. (2015) suggested that an effective way to increase fluid intake amongst older people is by making use of multicomponent interventions, since it is improbable that a single intervention would be useful and effective. Nonetheless, Bunn et al. (2015) underlined the dearth of evidence related to hydration practices to sustain those living in older adult care homes to drink sufficient fluid. This is also reflected locally, where knowledge and evidence of hydration practices in care homes is scarce. One has to bear in mind that the climate in Malta is a Mediterranean one, characterised by hot, dry summers. This climate increases the risk of dehydration as it poses an impact on hydration requirements (Schols et al. 2009). Consequently, it is crucial that current hydration practices are explored with a view to informing effective hydration policies and practices.

Method

A scoping review was conducted to explore hydration practices amongst older people in residential care homes. Scoping reviews are considered a valid approach in synthesising evidence (Munn et al. 2018). This methodology was deemed appropriate for the purpose of our inquiry since we wanted to determine emerging evidence on hydration practices and explore any gaps that might be addressed by future research.

This scoping review is guided by the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). The authors explained this method as a way of ‘mapping’ pertinent literature in a field of interest. Via a series of iterative steps, chosen evidence regarding the topic of interest is synthesized to enable and facilitate education, practice, and future research suggestions (Coquhoun and O’Brien 2010). The framework utilised is divided into five main stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying the relevant studies;

(3) selecting the studies; (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results (Arskey and O’Malley 2005).

Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

The research question focused on the way in which the search strategy was planned: ‘What is known from the existing literature regarding the practices that promote hydration in older adult residential care homes?’

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

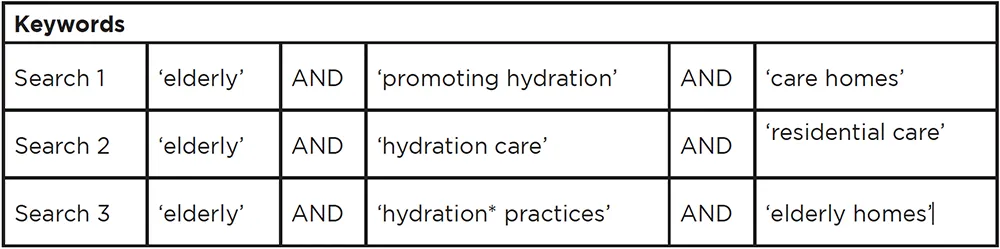

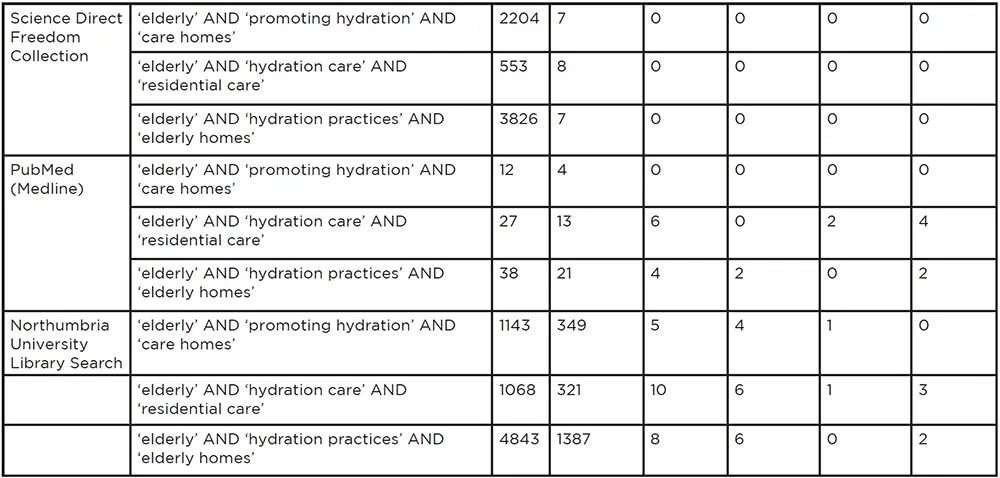

Comprehensive scoping reviews seek to attain literature from a selection of electronic databases in order to identify primary studies and reviews appropriate for answering the main research question (Colquhoun et al. 2014). The following ten databases were utilised to recognise significant and relevant evidence available: CINAHL, ProQuest: Health Research Premium Collection, SAGE Premier, Cochrane Library, Springer Journals, WILEY Interscience, BioMed Central, Science Direct Freedom Collection, PubMed (Medline), and Northumbria University Library Search. The keywords used to search the databases with the Boolean operator ‘AND/OR’, are illustrated in Table 1. These were agreed following discussion among the three researchers.

Table 1: Keywords

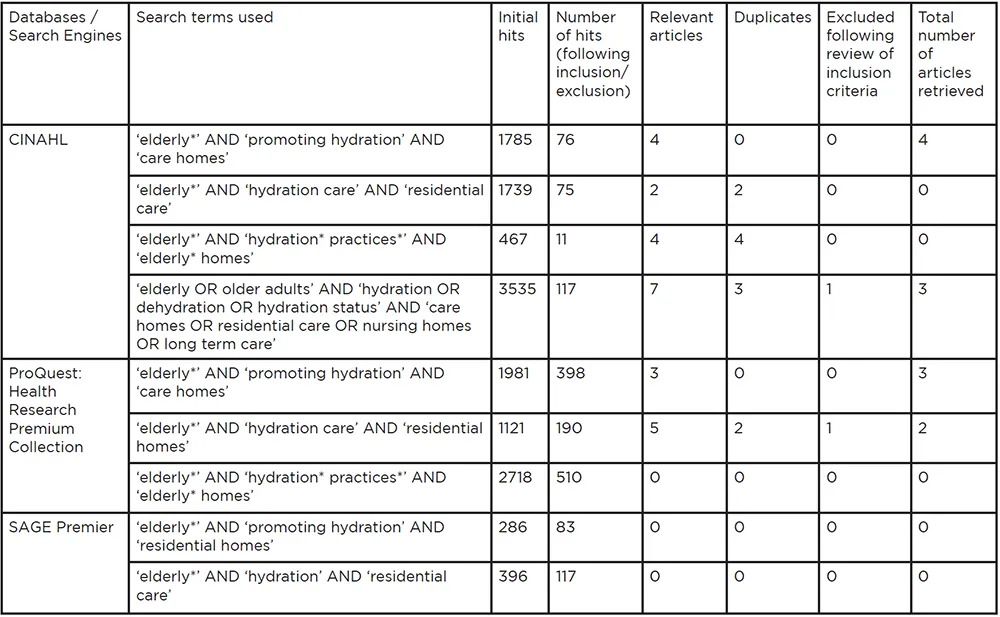

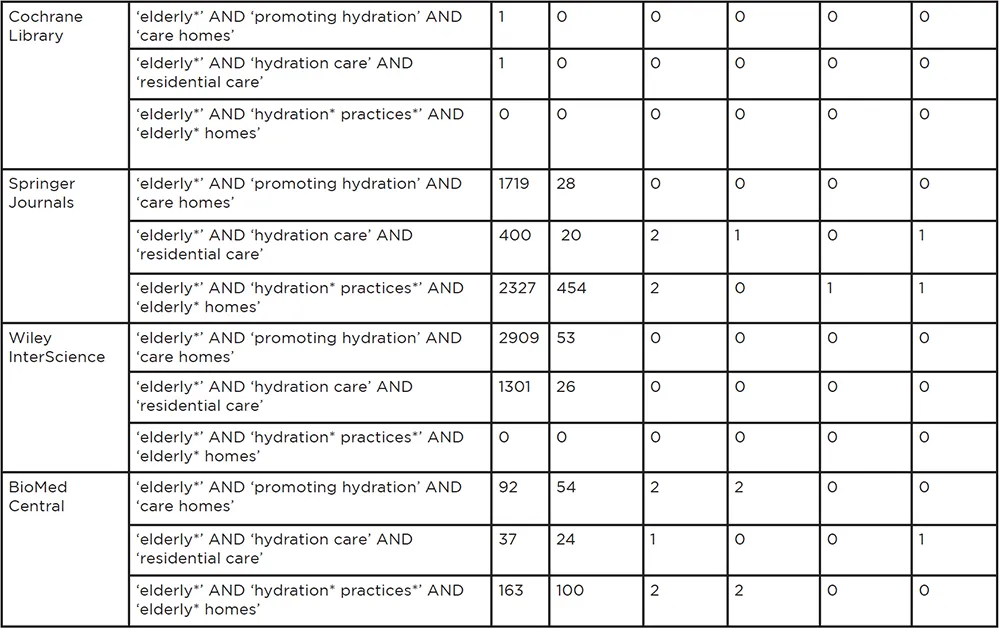

Truncation of selected search terms ensured that all variations of a word were included in the search. For searches that yielded few or no results, refining of the search terms was done for specific databases. Table 2 provides a detailed outline of the search strategy.

Table 2: Detailed Search Strategy

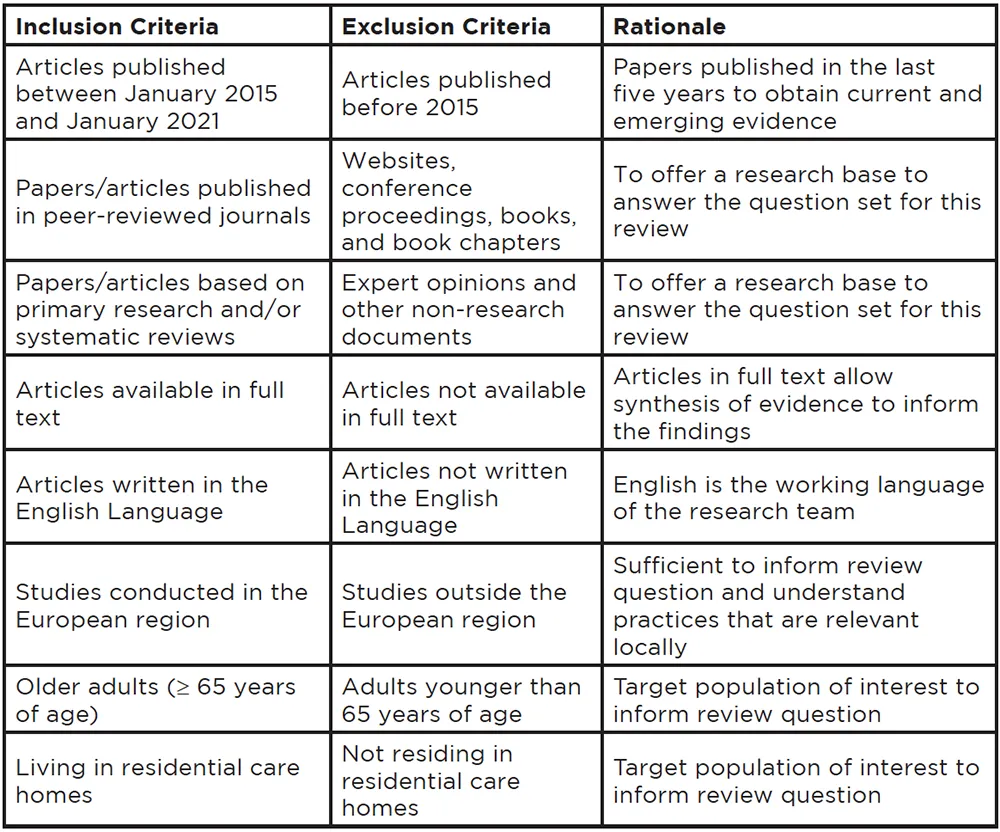

The research team established and agreed on the inclusion and exclusion criteria illustrated in Table 3. Limits in the search of the databases included only articles published in peer-reviewed journals and available in full text. Websites, expert opinions, conference proceedings, books and book chapters, and other non-research documents were excluded to limit the search and provide a quality evidence-base to our research question. Only articles written in English were included, as this is the working language of the research team. A further limit was the inclusion of studies in the European Region, as this was deemed suitable to inform the focus of this review. Moreover, by searching recent literature published between January 2015 and January 2021, relevant and current studies were identified.

Table 3: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Stage 3: Study Selection

Following the inclusion criteria set in our databases search (Table 3) the research team reviewed all the papers independently. This was followed by thorough discussions among the research team on which papers were pertinent to the focus of this review. This process is further detailed in the results section. In an attempt to offer a research evidence-base to our review, papers based on primary research, systematic reviews and literature reviews were included. Expert opinions and other non-research documents were excluded. Study participants had to be older adults (≥ 65 years of age) and living in residential care homes, as this was the population we were investigating. With regards to the focus of the papers, we only included articles that provided evidence primarily on hydration practices, and those which focused more prominently on nutritional intake were excluded.

Stage 4: Charting the Data

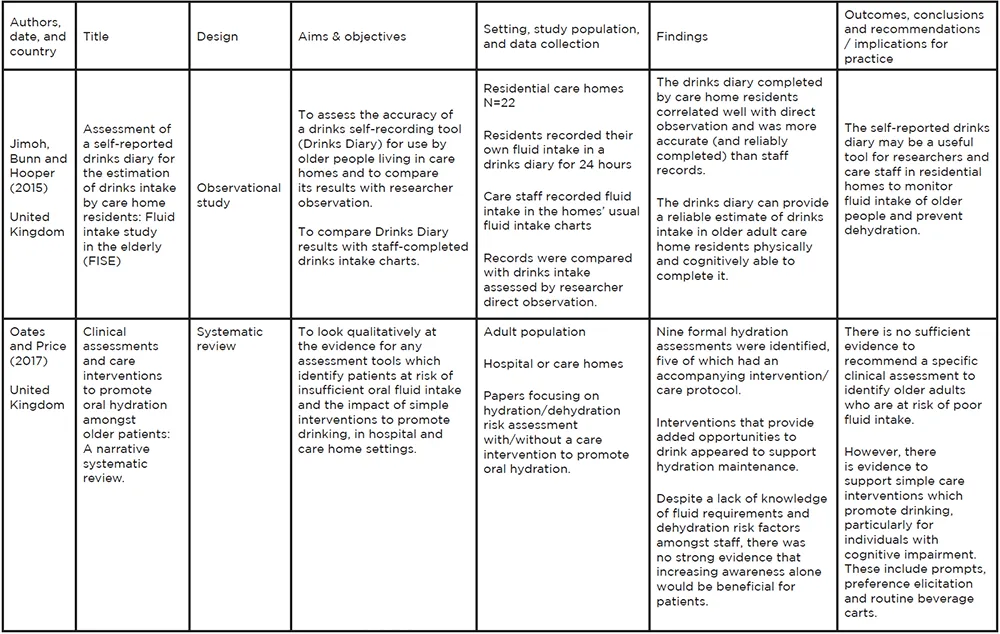

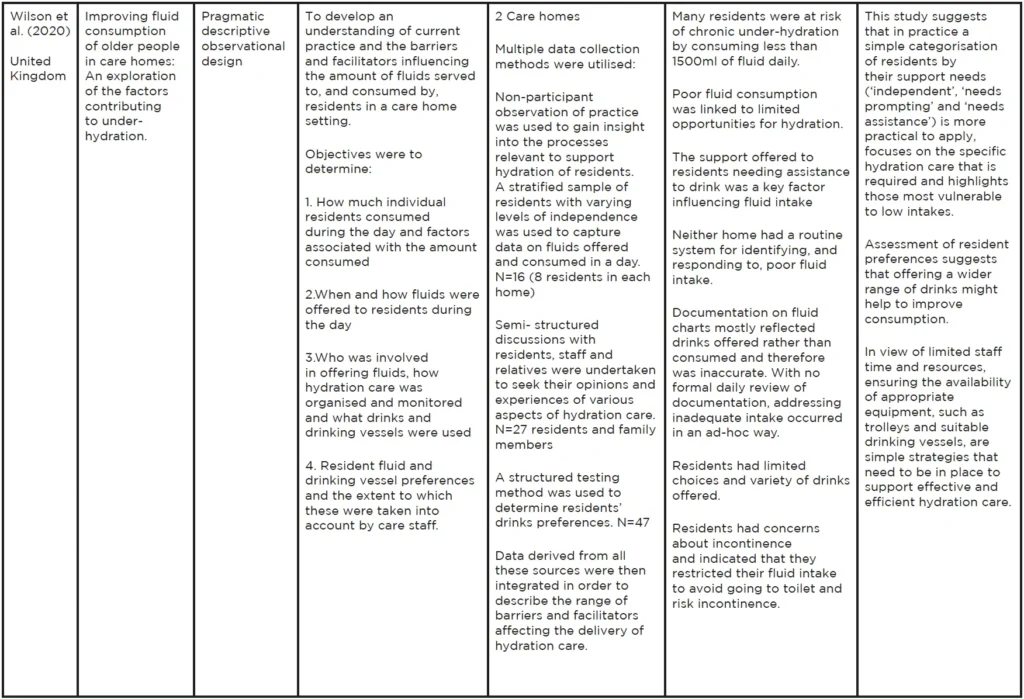

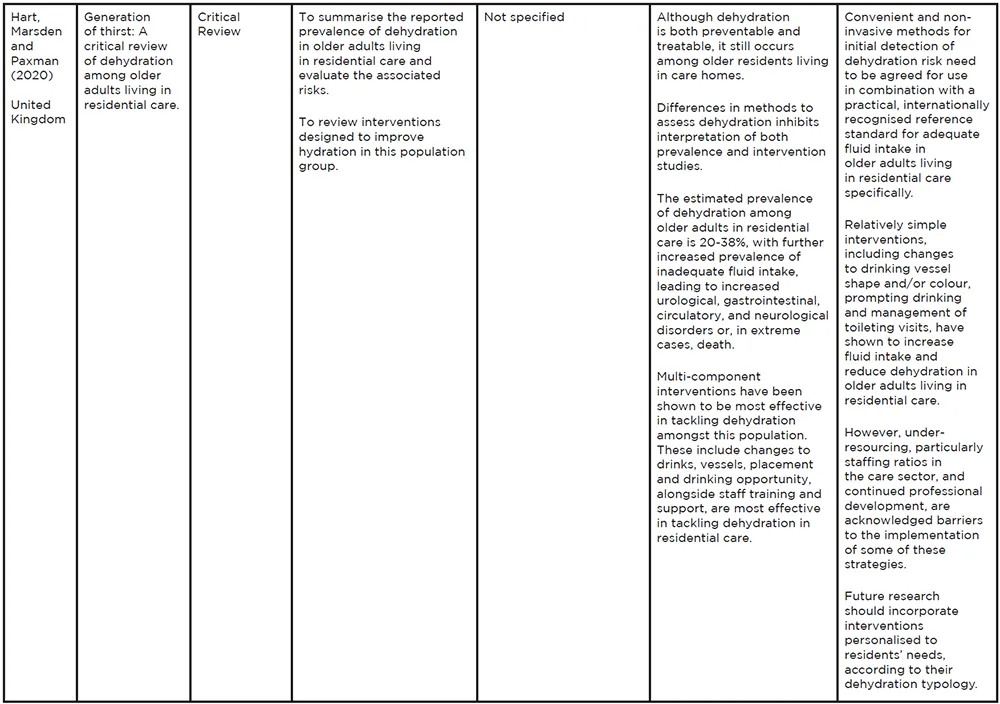

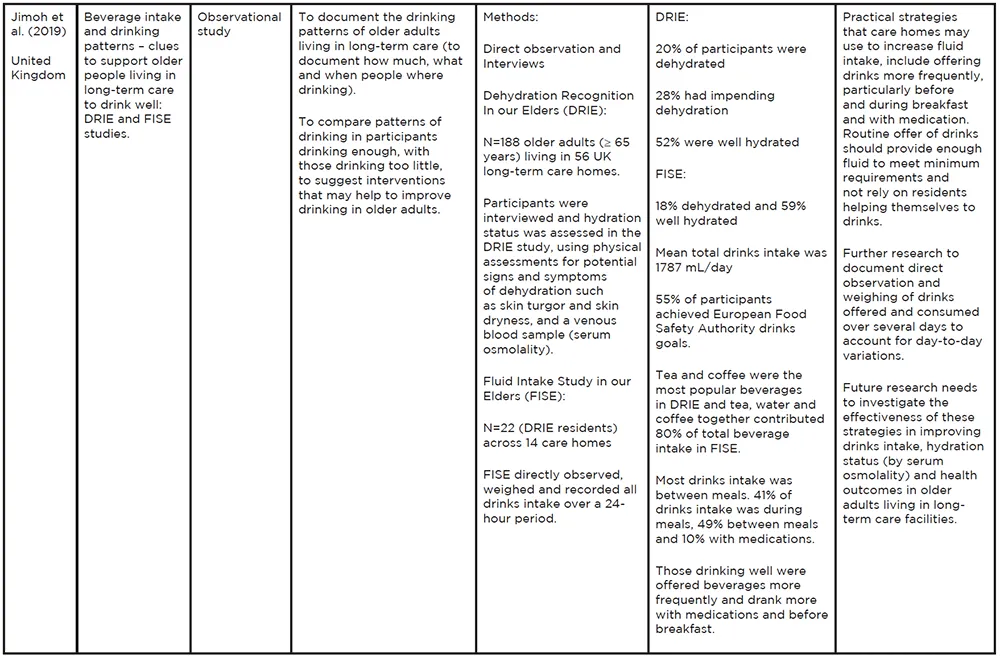

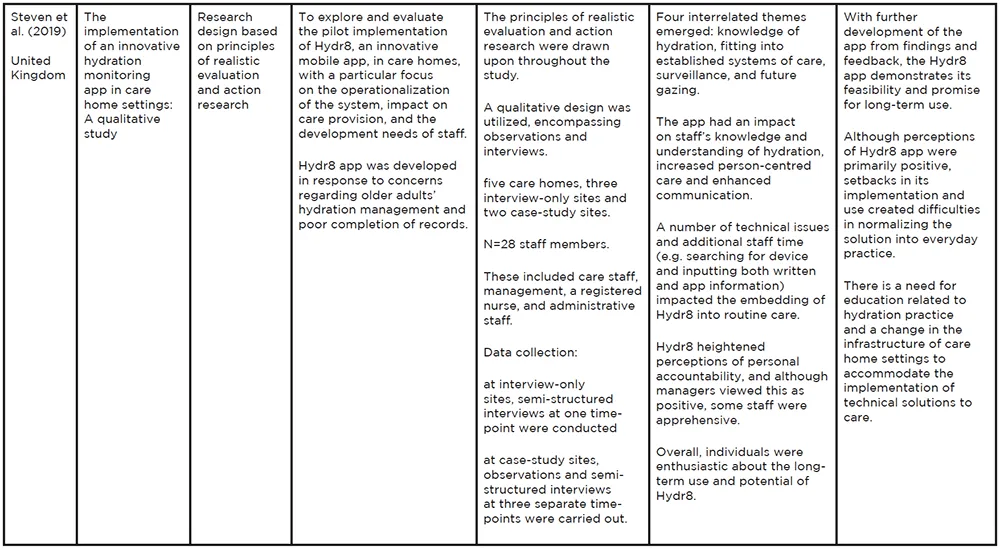

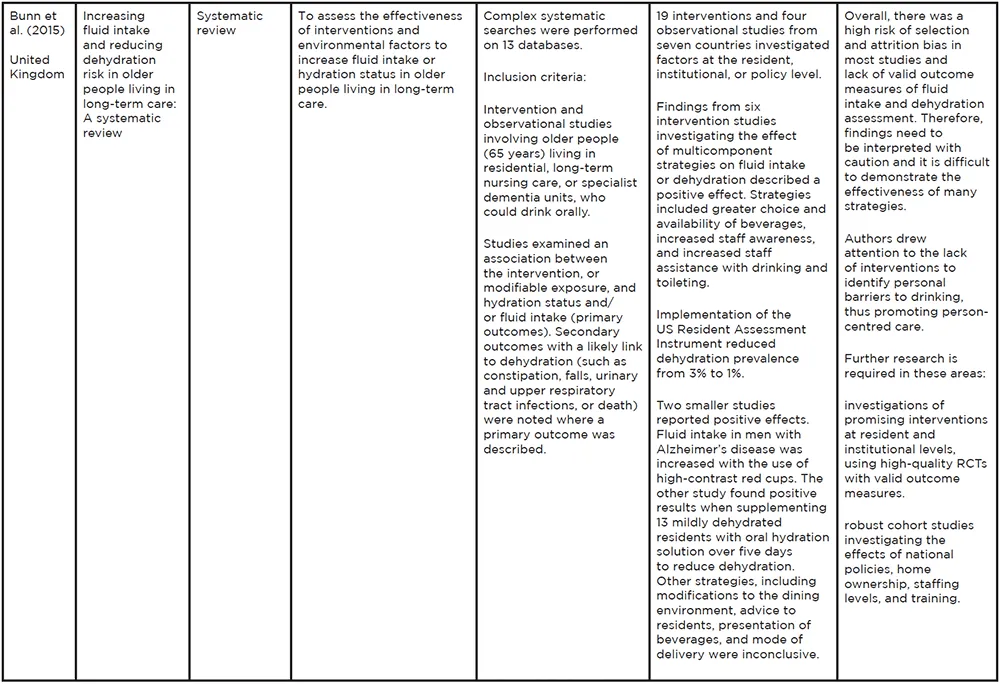

The final 11 papers selected for our scoping review were subjected to data charting to generate a descriptive summary of the results obtained from primary search (Table 4). Ritchie and Spencer (1994) explained the term ‘charting’ as a technique for integrating and interpreting data by scrutinizing, mapping, and sorting material in correspondence to key issues and themes. Three main themes that correspond with the research question, were created with the following headings: (1) approaches to intervention, (2) assessment of hydration status, and (3) strategies to promote hydration. All 11 final inclusion studies were reviewed and allocated under their respective theme. These themes were later used to detect gaps and inconsistencies represented in the existing frameworks, for future consideration and modification.

Studies were not measured in terms of their quality, as the main intent of this scoping review is to map the research carried out in this area. However, the strengths and limitations of the studies were considered when exploring gaps that might be addressed by future research locally.

Stage 5: Collating, Summarising, and Reporting the Results

Following data extraction, the study results were gathered, reviewed, and summarised. Analysis of the included studies involved qualitative thematic analysis and the results are presented as a narrative synthesis. The final stage involved a discussion of the results and the implications for practice, education, and research (Arksey and O’Malley 2005).

Table 4: Data charting

Results

Selection of Included Studies

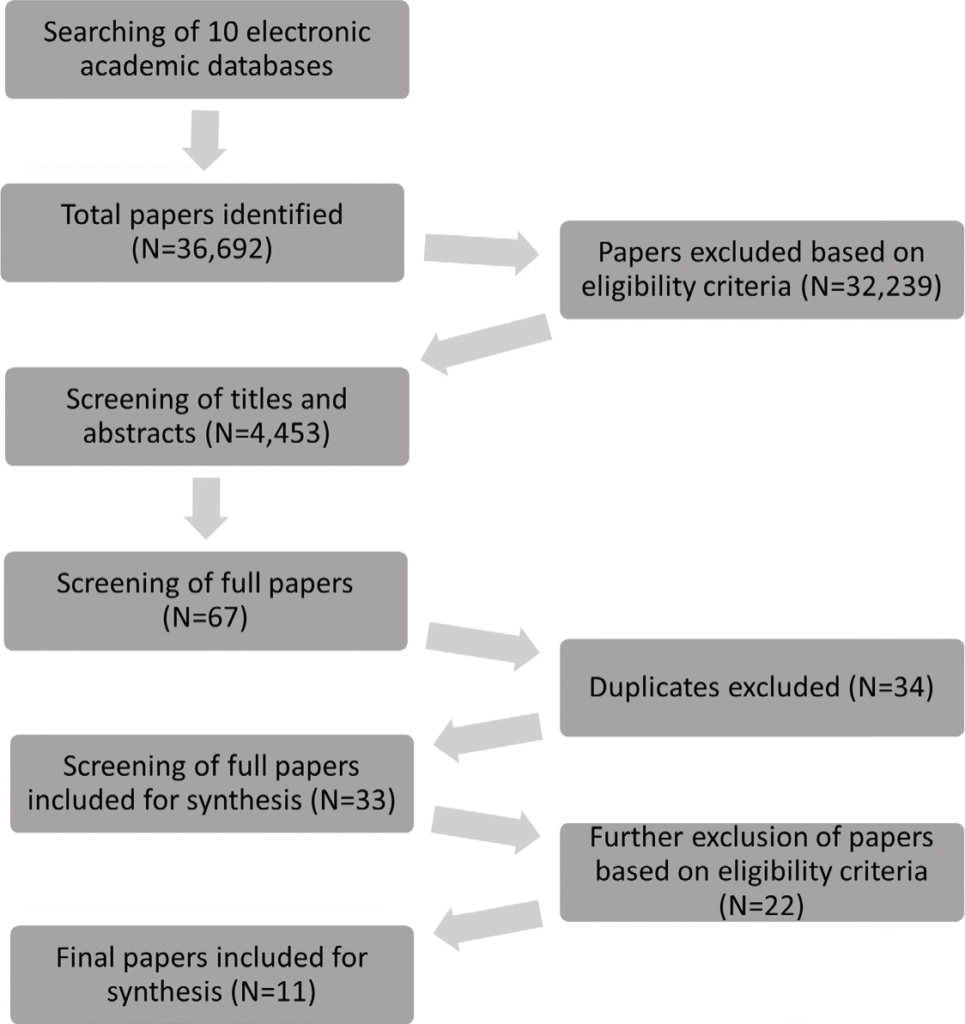

The total number of papers obtained from the initial search of the ten electronic databases was 36,692. After applying the eligibility criteria (Table 3), the researcher team screened 4,453 papers by briefly reviewing the titles and abstracts. The number of potentially relevant papers was reduced to 67. Following the elimination of duplicates (n=34), the remaining 33 papers were further analysed for relevance by reviewing the full text. This was done independently by the three researchers and agreement was reached for the final inclusion of 11 papers. This process is illustrated in Figure 1 and was adapted from Davis et al. (2009).

Characteristics of Included Studies

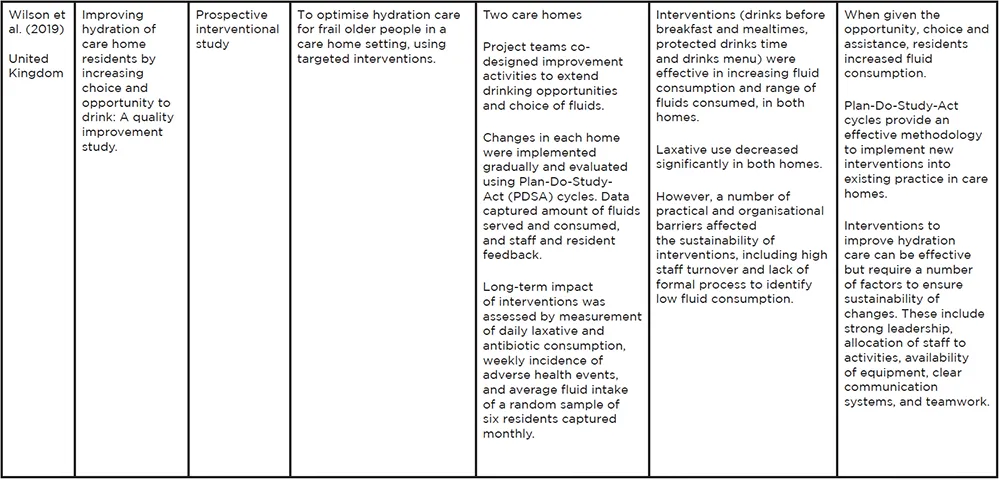

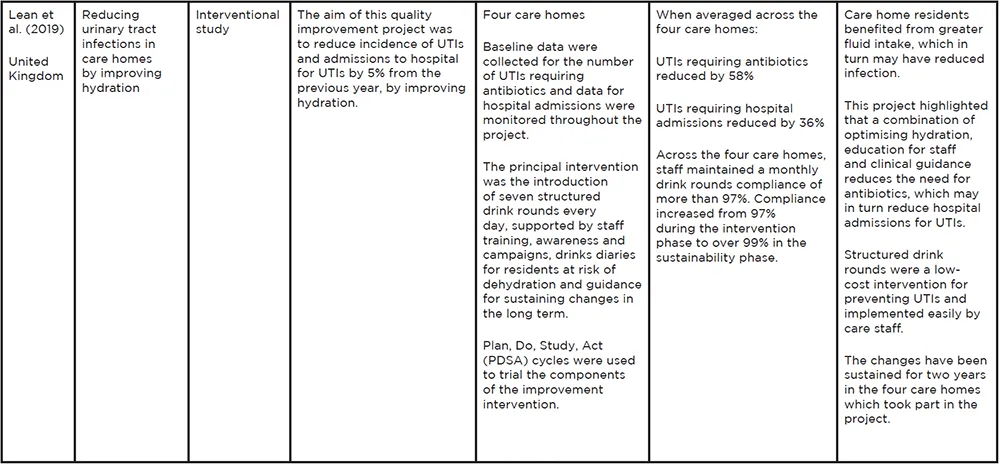

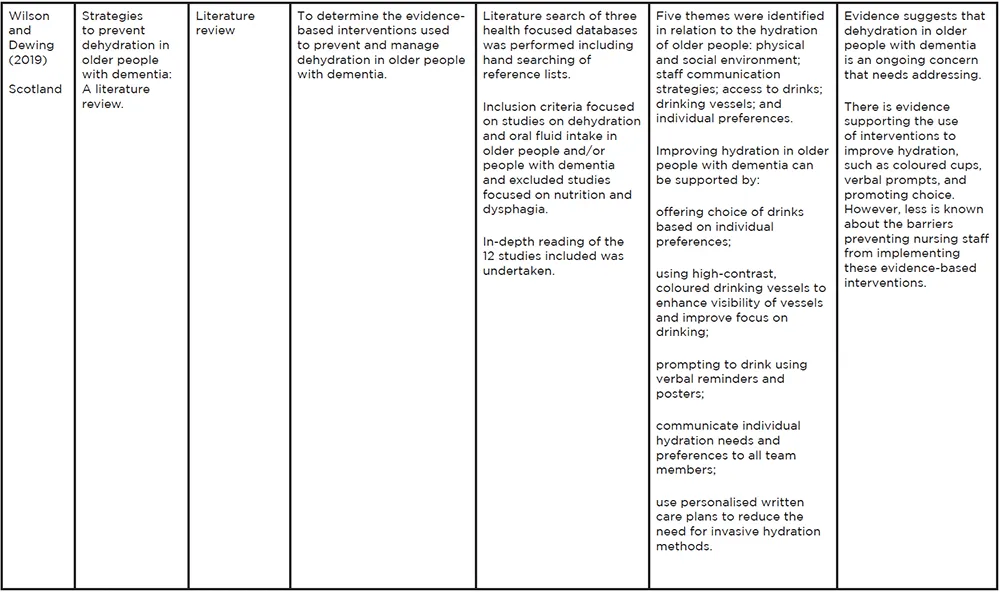

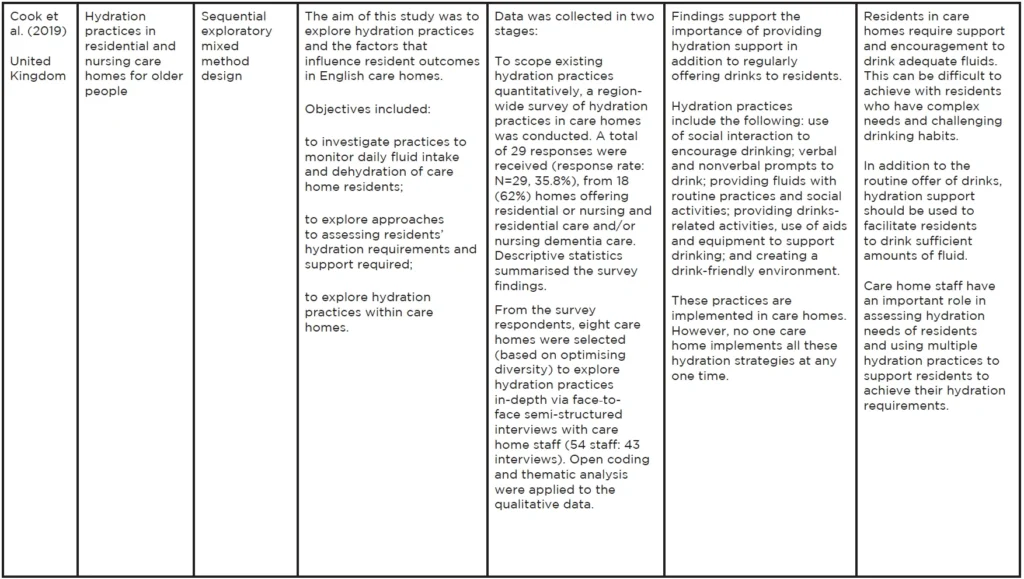

The 11 studies selected for analysis were based on work carried out in the United Kingdom between 2015 and 2020. Four studies adopted an observational study design (Wilson et al. 2020; Cook et al. 2019; Jimoh et al. 2019; Jimoh, Bunn and Hooper, 2015), whilst two were interventional studies (Lean et al. 2019; Wilson et al. 2019). One study was based on principles of realistic evaluation and action research (Steven et al. 2019). The rest of the papers included two systematic reviews (Oates and Price 2017; Bunn et al. 2015), one literature review (Wilson and Dewing, 2019), and one critical review (Hart, Marsden and Paxman, 2020). The other characteristics of the final chosen studies are summarised in Table 4.

Figure 1: Search flow diagram adapted from Davis et al.(2009)

Findings

The purpose of this scoping review is to examine the scientific evidence available on hydration practices in care homes for older adults. To carry this out seven primary studies, two systematic reviews, one literature review, and one critical review have been included. A look at the salient findings is considered here.

Wilson et al. (2019) investigated the impact of extending drinking and choice of drink opportunities in two care homes. The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) was the selected tool to support sustainable change and for evaluation. Data collection was done over seven PDSA cycles and focused on the amount of fluids offered as well as feedback from residents and care home staff. Long-term effects of extending drinking opportunities were assessed by monitoring the consumption of antibiotics and laxatives, and adverse health events on a weekly basis as well as the random sampling of six residents monthly to assess their average fluid intake. The interventions introduced, pre-breakfast drinks, drinks after meals, protected drinking times, as well as introducing a drinks menu for both hot and cold drinks, resulted in a sustained increase of fluids offered both in amount and selection.

The PDSA cycle was also implemented in a study carried out by Lean et al. (2019). Seven structured drink rounds were introduced to encourage regular opportunities of hydration for all residents as the main intervention to reduce urinary tract infections. The four care homes that participated in this study maintained a high level of compliance of the structured drink rounds. This intervention, strengthened with staff training, awareness, and drinks diaries reduced the need for residents to take antibiotics for urinary tract infections also surpassed the target of reducing admissions to hospital by 5% due to urinary tract infections.

Cook et al. (2019) used a sequential exploratory mixed method design to explore existing hydration practices. The approaches and strategies identified were, namely: encouraging drink through social interaction; providing prompts to drink; offering additional fluids with medications and during meals; providing a variety of drinking vessels and aids to support drinking; offer beverages with activities; organising drink-related activities; and creating a “drinking conducive environment”. It was noted that the variety of strategies and interventions was good, as was the commitment of the staff to follow these through. However, challenges were noted with regards to care home staff’s knowledge on hydration requirements. Residents with complex health needs require a lot of additional support to achieve their recommended fluid intake, and the implementation of the strategies and interventions were noted to be solitary and not supportive of each other. This was noted to have an impact on the overall aim of residents successfully drinking adequate fluids daily. The implementation of an innovative hydration monitoring application ‘Hydr8’ was explored by Steven, Wilson and Young-Murphy (2019). Five care homes participated in this qualitative study that utilised interviews and observations at three-time points. Despite the technical challenges encountered, the application had a positive impact on the implementation in day-to-day practice, where there was a noted improvement in hydration management and maintaining of records. The study also highlighted that although care home staff were keen on the long-term implementation of the application in practice, an element of apprehension linked to individual accountability and the usage of the application was also noted. Two key points put forward here are the importance of ensuring that the staff have the appropriate level of competence in hydration practices, as well as ensuring that adequate infrastructure is in place to support the efficient use of technical applications in everyday practice for its sustainable use.

Jimoh, Bunn and Hooper (2015) carried a fluid intake study in older people by using a three-prong approach; direct observation, asking the residents to document their fluid intake using a standardised tool, and evaluating fluid intake charts kept by the staff. This was the first study done that asked residents to document their fluid intake. The findings of the study indicated that there was a positive correlation between direct observations and the documentation carried out by the residents. The direct observations were deemed the benchmark for comparison following the pilot study. On the contrary, not only was completion and submission of fluid intake charts filled in by staff limited, but those that were submitted demonstrated low correlation with the findings from the direct observations and therefore indicated significant limitations in appropriate documentation skills, as well as overall awareness on the significance of accurate monitoring of fluid intake.

An exploration of factors contributing to under-hydration in two care homes was carried out by Wilson et al. (2020). A pragmatic descriptive observational design using multiple data collection methods was utilised, where data was collected through non-participant observation of practice, semi-structured discussions, and a structured testing method to determine residents’ drinking preferences. The findings indicated that fluid intake charting was done for a small number of residents identified as being vulnerable, where the documentation often reflected the fluids that were offered and not consumed. The mean intake during the day was 1,031ml, well under the required minimum intake. This was noted to be compounded further as a resident allocation system was not implemented in either home, and no specifications were in place with regards to regular documentation, updating, and review.

Understanding the drinking patterns of residents residing in long-term residential care was the main aim of Jimoh et al. (2019). Their study sample included 188 residents aged 65 years and older from across 56 long-term residential care homes. The hydration status was assessed in the Dehydration Recognition in our Elders (DRIE) study. In 22 DRIE residents the Fluid Intake Study in our Elders (FISE) was directly observed over a period of 24 hours. Mean total drinks was 1,787ml and was notably higher in men than in women. The highest intake of fluids occurred between meals including medications (59%). Twelve participants from the FISE study achieved the minimum fluid intake recommendations as put forward by the European Food Safety Authority. Factors that were observed to support good fluid intake were being offered fluids frequently, drinking more with medications, as well as before breakfast.

In a systematic review carried out by Hart, Marsden and Paxman (2020) an assessment of different screening tests of dehydration in older adults found that bioelectric impedance analysis, missing drinks between meals, and experiencing fatigue to be the most sensitive and specific indicators of dehydration. The findings were noted to be limited as the reference standards for required fluid intake varied in the literature and ultimately no tests were conclusive in making a diagnosis. It was noted, however, that observational symptoms such as mouth, eyes, skin, and self-reported symptoms are often used by care home staff to monitor hydration. It was highlighted, though, that this approach may not be accurate in identifying dehydration resulting from low intake.

Oates and Price (2017) found in their narrative systematic analysis that dehydration prevention activities are not supported by a strong evidence-base. Despite a small sample size, with an unclear environmental context, and unclear standard reference for clinical values, the need to highlight the importance of hydration is clear. Emphasis on the responsibility of care home staff in supporting adequate fluid intake, the need for staff education on hydration, and related practices improved clinical documentation, and policy and audit systems were evident needs identified in the analysis carried out here. Residents with cognitive impairments were noted to be at a higher risk of dehydration and the literature indicates that they may benefit from increased opportunities of supported drinking.

The exploration of strategies to prevent dehydration in older people with dementia (Wilson and Dewing 2019) indicated that there is evidence supporting the use of colour- coded cups, as well as verbal cues. The themes that emerged were the physical and social environment; communication strategies; access to drinks; drinking vessels; and individual preferences. Although the emerging themes are supportive of essential nursing and care interventions, the literature indicates that these are not widely implemented. Nurses need to adopt person-centred approaches as a strategy to improve fluid intake, and the physical and social environment also have an impact on fluid intake, where lack of interaction was linked to reduced fluid intake. In addition, an effort needs to be made to reduce isolation during mealtimes.

Bunn et al. (2015) implemented a systematic review of intervention based on observational studies that investigated modifiable factors related to fluid intake in residents aged 65 years and older living in long-term care and who were able to drink orally. Six of the nine intervention studies included in the review found that multi-component strategies on fluid intake or dehydration have positive outcomes. These strategies included greater choice and availability of fluids, increased staff awareness, as well as increased staff support with both drinking and toileting. The review acknowledged a high risk of bias due to selection and attrition bias and lack of valid outcome measures of fluid intake and dehydration assessment. Emphasis on the need to investigate dehydration prevention, effectiveness of policies, staffing levels, and training needs are required. It is also noted that the lack of interventions to identify and target personal barriers to drinking needs to be explored further.

Discussion

Strategies to Promote Hydration

Cook et al. (2019) identified a range of hydration practices that can be included in the daily routine of care homes. The literature highlights that care home staff have an important role in implementing multiple hydration practices to ensure residents achieve adequate fluid intake (Hart, Marsden and Paxman, 2020; Oates and Price 2017; Bunn et al. 2015). The range of practices identified by Cook et al. (2019) however do not support each other and therefore residents consistently fall short of achieving their recommended fluid intake. This finding was also noted by Wilson et al. (2020), Jimoh et al. (2019) and Wilson and Dewing (2019). Bunn et al. (2015) identified a widespread gap in the availability and effectiveness policies. Oates and Price (2017) emphasised that poor documentation was noted to have an impact on the effective monitoring of fluid intake and was thus a critical factor leading to dehydration. This finding supports the work done by Jimoh, Bunn and Hooper (2015).

Hart, Marsden and Paxman (2020) reiterate that the risks resulting from dehydration are significant and can lead to loss of cognitive function, resulting in premature mortality. In their review, the literature indicated that multi-component strategies have been shown to be the most effective approach to preventing dehydration. It was also noted that strategies need to be in place to identify dehydration as early as possible and those who are at risk. Hart, Marsden and Paxman (2020) advocate and recommend that a combination of practical, widely recognised reference standards for adequate fluid intake need to be established, particularly for residential care homes. This echoes the recommendations put forward by Cook et al. (2019).

In response to concerns regarding hydration management and accurate record keeping, an innovative hydration application “Hydr8” was implemented in five care homes. Steven, Wilson and Young-Murphy (2019) explored the experience of this implementation. Despite some technical mishaps, the study did indicate that this technology could be a long- term mechanism that promotes hydration practices and improves record keeping. The application was also noted to improve communication strategies among staff. Areas that need to be addressed prior to wider implementation are technical design to ensure an improvement in the quality of care that is sustainable, as well as staff education to promote confidence and ownership. Oates and Price (2017) reported an initiative taken by the NHS East of England in 2011 where a fluid care bundle was developed. This included an audit tool, patient information, and nine principles to assist with fluid management: focus on individual patient needs; assess all patients; facilitate hydration; maintain accurate fluid balance; provide guidance documents for staff; provide information leaflets for patients and relatives; communicate relevant changes in the patient condition; perform fluid assessment audit; analyse fluid related adverse events. No data is available on the impact this had on hydration practices and adequate fluid intake.

Wilson et al. (2019) assert that the use of PDSA cycles to test changes such as embedding strategies, even simple approaches, into routine practice to improve fluid consumption is an effective methodology. They highlight that making changes to routine practice is not easy and requires effective leadership, role modelling and mentoring, organisational support, and teamwork. Their study demonstrated that simple, inexpensive measures such as protected drinking time and a drinks menu can be effective, practical, inexpensive strategies that improve fluid intake without negatively affecting the workload of the care staff. The PDSA methodology was also adopted in a study to assess the impact of the introduction of seven structured drink rounds to reduce the prevalence of urinary tract infections (Lean et al. 2019). The rounds were also complemented with theming and decorating of trolleys to attract attention. The themes were changed regularly to reflect events, occasions, and seasons. In addition, the drinks rounds offered a variety of hot and cold drinks in colourful mugs and cups. Alternatives such as ice lollies and milkshakes, that also increase fluid intake, were additional options. This project lasted two years and resulted in 100% compliance in all four care homes and was achieved with strategies to optimise hydration, education for staff, and clinical guidance. Lean et al. (2019) also point out that the success of this study and outcomes that led to the homes surpassing their target of reducing urinary tract infections was attributed to care home staff co-designing the drink rounds for each home respectively.

Bunn et al. (2015) underlined their concern as their findings indicated that further investigations were required into dehydration prevention at residential, institutional, and national policy levels. In addition to this, further research was also recommended by Bunn et al. (2015) to explore the effects of national policies, care home management, staffing levels and training requirements. They acknowledged that developing high quality research in care homes is challenging however and is necessary to improve the hydration status of residents. The findings of more recent studies and reviews indicate that this is still a valid concern.

Assessment of Hydration Status

Nursing assessments are a common tool used to document various aspects of patient care including wound management and parameter charting (Hart, Marsden and Paxman 2020) so as identified by Oates and Price (2017) it is remarkable that there is no standardised assessment tool to monitor fluid intake or changes in hydration status in older persons. Oates and Price (2017) found in their systematic analysis that dehydration prevention activities are not supported with a robust evidence-base and individuals are noted to have an inadequate hydration status when a negative fluid is documented. They ascertain that clinical assessment of hydration status and risk has been promoted by researchers, policy makers, and health authorities but has not been addressed in a coordinated, evidence-based approach. Moreover, challenges in establishing an effective, practical, single bedside, dehydration risk assessment due to different patient groups and settings are widely reported. The critical review by Hart, Marsden and Paxman (2020) demonstrates similar findings. The aim of their review was to identify different screening tools for assessing dehydration. The results showed that no test was consistently useful in diagnosis due to the diversity in reference standards, lengths of observation, implementation of assessment methods, as well as differing definitions of what are classified as fluids. The literature affirms that inadequate fluid intake in care homes varies from 39% to 100%, as is attributed to the heterogeneity in assessment methods, standards and establishing what constitutes adequate fluid intake.

Jimoh, Bunn and Hooper (2015) compared drinks diary to direct observation of fluid intake to determine effective methods of assessing fluid intake. A comparison was also done among staff documentation and direct observation. The findings of this study strengthen the concerns highlighted by other researchers (Oates and Price 2017) with regards to competent and complete documentation by staff. While the drink diaries correlated positively with the direct observation, the charts completed by the staff were minimal and those that were completed were not done so accurately. While the drinks diary method is a possibility assessment approach that can be considered for wider use, it is worrying that these discrepancies were noted from staff. Jimoh, Bunn and Hooper (2015) propose that direct observation is the current ‘gold standard’ in ascertaining accurate assessment of fluid intake.

A pragmatic descriptive observational design was the methodology adopted by Wilson et al. (2020) to explore factors contributing to under hydration. The study sample included two care homes with residents ranging from frail to those with mild or moderate cognitive impairment. The findings revealed that neither home had a system in place for identifying and responding to low fluid intake. Fluid charting was only implemented for a notably small number of residents and documentation on intake was more reflective of the drinks that were offered rather than consumed by the resident. In addition, neither home had a system of ‘resident allocation’ in place, making observation of fluid intake by assigned staff challenging. It also resulted in poor fluid intake to be addressed inconsistently.

Interventions that Promote Hydration

In their critical review, Hart, Marsden and Paxman (2020) found that multi-intervention approaches that are person-centred are identified as being the most effective in preventing dehydration. Person-centred approaches to interventions include drinking vessel type and size, drink range and proximity, as well as continence support (Cook et al. 2019; Wilson and Dewing 2019; Oates and Price 2017; Bunn et al. 2015). Reference is made to an observational study by Mentes (2006) where a typology of hydration challenges for different groups was produced with identified interventions that can be implemented according to the status of the resident. The subgroups identified are independent, cognitively impaired, dysphagic, physically dependent, sipper, fears incontinence, and terminally ill. Interventions include education and a choice of preferred beverages for independent residents, frequent offers and activities for the cognitively impaired, swallowing exercises and foods rich in fluid for those who are dysphagic, mobility aids to promote movement for the physically impaired, as well as a sports cup for drinking, frequent opportunities for drinking, offering preferred beverages and, activities for those identified as sippers, exercises and education for residents who are concerned about incontinence, and a focus on preference in end-of- life care. This observational study did not focus on the effectiveness of the interventions; however, the combined quantitative and qualitative data identified the importance of individualised care when selecting interventions. The need to focus on establishing individual needs and suitable interventions to prevent dehydration is widely reported.

Hart, Marsden and Paxman (2020) recommend that future research explores this typology further, which would also aim to address the lack of evidence based on this practice. In the study carried out by Wilson et al. (2020) a total of 294 individual episodes of drinking opportunities were observed over a period of five days. It was noted that more than one drink was offered during mealtimes in just 11.6% of episodes. There was a notable increase of drinks served during mealtimes, 75% of episodes as opposed to in- between meals, where episodes observed were 39. Even fewer episodes were noted before breakfast or mid-morning, and it was also recognized that residents who were in the communal area had more drinking opportunities than those who were in their rooms. The opportunity for individual choice was limited with 55% of drinks served being tea, and options such as coffee, juice, and milk not readily available. The findings presented here reaffirm the challenges presented in previous literature (Wilson et al. 2018; Oates and Price, 2017) as well as factors that contribute to under-hydration.

Interventions supported with regular prompts by care home staff reduced episodes of dehydration, with or without the use of beverage carts (Oates and Price, 2017). Frequent support also resulted in a reduction in falls, urinary tract infections, and the use of laxatives, where all of these are indicators of improved hydration status (Lean et al. 2019; Cook et al. 2019; Jimoh et al. 2019; Oates and Price, 2017). Wilson and Dewing (2019) found evidence that interventions supporting nursing care included coloured cups and verbal prompts, however the barriers preventing the implementation of these interventions was less understood.

Acknowledging that drink intake is generally low in care homes, Jimoh et al. (2019) investigated drinking patterns and intake by comparing those residents who drink well and those who do not. Interventions that were noted to have a positive correlation to those residents who drank well included choice of drink, increased opportunities and timings of these opportunities, availability, and access to drinks, aside from routine provision. Barriers to adequate hydration included continence concerns, limited choice, physical barriers, and cognitive impairment. These findings further support the evidence that supportive care staff, choice and opportunity are important mechanisms to improve hydration status (Hart, Marsden and Paxman 2020; Jimoh et al. 2019; Wilson et al. 2018; Bunn et al. 2015).

Conclusion

The interest in hydration practice was notable during this review. However, despite this steadfast interest the literature indicates that challenges in reducing dehydration, implementing consistent assessment techniques, and interventions remain heterogeneous. This has an impact on the overall wellbeing of residents in care homes as it increases their risk of adverse events. The evidence-base is limited, therefore leaving gaps and uncertainty in standards and benchmarks that will support hydration practices in care homes as well as other care settings. Methods for the early detection of hydration and corrective measures as well as established multi-component strategies need to be standardised. This is essential in all aspects of practice, more notably however with regards to assessment, continence support, increasing opportunities and choices to drink, as well as having care home staff that are supportive and competent in hydration practices. In addition, future research on addressing individual needs of residents adopting a person-centred approach is highly recommended.

Locally, the evidence-base is limited and there is a need for more research on the topic of hydration requirements particularly in care practices. Audit data are also lacking, where the absence of such information continues to strengthen the rationale supporting the need to explore hydration practices in older adult residential care homes. It is recommended that these studies are implemented prior to establishing the necessary standardisation in care procedures as well as identifying benchmarks, thus providing relevant evidence-based contributions to an important yet much overlooked aspect of care.

Strengths and Limitations

We acknowledge the limitations of adopting a scoping review approach, primarily in terms of the lack of formally evaluating the quality of evidence. Scoping reviews are concerned with obtaining breadth of literature (Munn et al. 2018). In our review we therefore included a literature review and a critical review, which did not lend itself well to traditional methods of quality appraisal. The inclusion criteria implemented in this scoping review, particularly language, date, and geographical limits, is also acknowledged as a limitation which might have excluded different considerations to hydration care. However, we set these limits to explore current and relevant evidence and additionally we included a vast set of databases for our search strategy, rendering strength to this scoping review.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our sincere appreciation to Dr Lorna Bonnici West for her continued support, expertise, and guidance

References

Arksey, H. and O’Malley, L. 2005. ‘Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework’,

InternationalJournalofSocialResearchMethodology, 8(1), 19-32.

Bourdel-Marchasson, I., Proux, S., Dehail, P., Muller, F., Richard-Harston, S., Traissac, T., and Rainfray, M. 2004. ‘One-year Incidence of Hyperosmolar States and Prognosis in a Geriatric Acute Care Unit’, Journal of Gerontology, 50(3), 171-176.

Bunn, D., Jimoh, F., Wilsher, S. H., and Hooper, L. 2015. ‘Increasing Fluid Intake and Reducing Dehydration Risk in Older People Living in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review’, Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(2), 101-113.

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus S., Tricco A. C. and Perrier, L. 2014. ‘Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting’, JournalinClinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291-1294.

Cook, G., Hodgson, P., Hope, C., Thompson, J., and Shaw, L. 2019. ‘Hydration Practices in Residential and Nursing Care Homes for Older People’, JournalofClinicalNursing, 28(7-8), 1205-1215.

Craig, A. H. 2011. ‘Hydration and Health’, JournalofLifestyleMedicine, 5(4), 304-315.

Davis, K., Drey, N. and Gould, D. 2009. ‘What Are Scoping Studies? A Review of the Nursing Literature’, International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(10), 1386-1400.

DRIE—Dehydration Recognition in our Elders. 2016. URL http://driestudy.appspot.com/cohort.html. (accessed 31st January 2021)

Gasper, P. M. 2011. ‘Comparison of Four Standards for Determining Adequate Water Intake of Nursing Home Residents’, Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 25(1), 11-22.

Godfrey, H., Cloete, J., Dymond, E., and Long, A. 2012. ‘An Exploration of the Hydration Care of Older People: A Qualitative Study’, InternationalJournalofNursingStudies, 49(10), 1200-1211.

Hart, K., Marsden, R. and Paxman, J. 2020. ‘Generation of Thirst: A Critical Review of Dehydration Among Older Adults Living in Residential Care’, NursingandResidentialCare, 22(12), DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/nrec.2020.22.12.6

Hooper, L., Bunn, D. K., Downing, A., Jimoh, F. O., Groves, J., Free, C., Cowap, V., Potter, J. F., Hunter, P.R. and Shepstone, L. 2016. ‘Which Frail Older People Are Dehydrated? The UK DRIE Study’, The Journals of Gerontology, 71(10), 1341-1347.

Jimoh, F.O., Bunn, D. and Hooper, L. 2015. ‘Assessment of a Self-Reported Drinks Diary for the Estimation of Drinks Intake by Care Home Residents: Fluid Intake Study in the Elderly (FISE)’, The Journal of Nutrition,Health and Aging,19(5), 491-496.

Jimoh, O.F., Brown, T.J., Bunn, D. and Hooper, L. 2019. ‘Beverage Intake and Drinking Patterns – Clues to Support Older People Living in Long-Term Care to Drink Well: DRIE and FISE Studies’, Nutrients,11(2), 447-461.

Lean, K., Nawaz, R.F., Jawad, S. and Vincent, C. 2019. ‘Reducing Urinary Tract Infections in Care Homes by Improving Hydration’, BMJ Open Quality, 8, 1-5.

Masot, O., Lavendan, A., Nuin, C., Escobar-Bravo, M. A., Miranda, J. and Botigue, T. 2018. ‘Risk Factors Associated with Dehydration in Older People Living in Nursing Homes: Scoping Review’, International Journal of Nursing Studies, 82, 90-98.

Mentes, J. C. 2006. ‘A Typology of Oral Hydration Problems Exhibited by Frail Nursing Home Residents’, Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 32(1), 13-19.

Mentes, J. 2013. ‘Hydration Management’, JournalofGerontologicalNursing, 39(2), 11-19.

Munn, Z., Peters, M.D.J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A. and Aromataris, E. 2018. ‘Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors when Choosing Between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach’, BMCMedicalResearchMethodology, 18, 143.

National Institute of Health Care and Excellence. 2013. Implementing a Policy for Identifying and Managing Malnutrition in Care Homes. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/sharedlearning/implementing-a-policy-for-identifying-and-managing-malnutrition-in- care-homes (accessed 5 January 2021).

Oates, L.L. and Price, C.I. 2017. ‘Clinical Assessments and Care Interventions to Promote Oral Hydration Amongst Older Patients: A Narrative Systematic Review’, BMC Nursing, 16(4), DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-016-0195-x

Paulis, S. J. C., Everink, I. H. J., Halfens, R. J. G., Lohrmann, C., and Schols, J. G. M. G. A. 2018. ‘Prevalence and Risk Factors of Dehydration Among Nursing Home Residents: A Systematic Review’, JournaloftheAmericanDirectorsAssociation, 19(8), 646-657.

Ritchie, J. and Spencer, L. 1994. ‘Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research’. In A.

Bryman and R.G. Burgess (eds.). AnalysingQualitativeData.Routledge (London), 173-194.

Robinson, S. B., and Rosher, R. B. 2002. ‘Can a Beverage Cart Help Improve Hydration?’,

GeriatricNursing, 23(4), 208-211.

Schols, J., De Groot, C., van de Carmen, T., and Olde Rikkert, M. 2009. ‘Preventing and Treating Dehydration in The Elderly During Periods of Illness and Warm Weather’, Journal of Nutrition,Health and Ageing, 13(2), 150-157.

Shaw, L., and Cook, G. 2017. ‘Hydration Practices for Quality Dementia Care’, Nursingand Residential Care, 19(11), 620-624.

Simmons, S., Alessi, C. and Schnelle, J. 2001. ‘An Intervention to Increase Fluid Intake In Nursing Home Residents: Prompting and Preference Compliance’, JournaloftheAmerican Geriatrics Society, 49(7), 926-933.

Steven, A., Wilson, G. and Young-Murphy, L. 2019. ‘The Implementation of an Innovative Hydration Monitoring App in Care Home Settings: A Qualitative Study’, JMIRMHealth, 7(1), DOI:10.2196/mhealth.9892

Thomas, D. R., Cote, T. R., Lawhorne, L., Levenson, S. A., Rubenstein, L. Z., Smith, D. A., Stefanacci, R. G., Tangalos, E. G. and Morley, J. E. 2008. ‘Understanding Clinical Dehydration and its Treatment’, JournaloftheAmericanMedicalDirectorsAssociation, 9(5), 292-301.

Vandervoort, A., Van den Block, L., van der Steen, J. T., Volicer, L., Vander Stichele, R. H., Houttekier, D., and Deliens, L. 2013. ‘Nursing Home Residents Dying with Dementia In Flanders, Belgium: A Nationwide Post-Mortem Study on Clinical Characteristics and Quality of Dying’, Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(7), 485-492.

Wilson, J., Bak, A., Tingle, A., Greene, C., Tsiami, A., Canning, D., Myron, R. and Loveday, H. 2019. ‘Improving Hydration of Care Home Residents by Increasing Choice and Opportunity to Drink: A Quality Improvement Study’, Clinical Nutrition, 38(4), 1820-1827.

Wilson, J., Tingle, A., Bak, A., Greene, C., Tsiami, A. and Loveday, H. 2020. ‘Improving Fluid Consumption of Older People in Care Homes: An Exploration of the Factors Contributing to Under-Hydration’, Clinical Review,22(3), 139-146.

Wilson, K. and Dewing, J. 2019. ‘Strategies to Prevent Dehydration in Older People with Dementia: A Literature Review’, Nursing Older People,32(1), 27-33.

Wolff, A., Stuckler, D. and McKee, M. 2015. ‘Are Patients Admitted to Hospitals From Care Homes Dehydrated? A Retrospective Analysis of Hypernatraemia and In-Hospital Mortality’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 108(7), 259-265.

Woodward, M. 2007. Guidelines to Effective Hydration in Aged Care Facilities. Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital (Heidelberg Heights, Victoria).

Wu, S. J., Wang, H. H., Yeh, S. H., Wang, Y. H. and Yang, Y. M. 2011. ‘Hydration Status of Nursing Home Residents in Taiwan: A Cross-Sectional Study’, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(3), 583-590.